Examining Effective Altruism: Part IV

Peter Singer: eugenics, bioethics, gene editing, euthanasia, infanticide. Meet the Godfather of Effective Altruism.

Happy Friday, everyone, and welcome back to Rounding the News. My name is Liam Sturgess and I will be your host for today's show, presented by Rounding the Earth.

Before we get started, I want to remind everyone that you can support the show by sending us a Rumble Rant or a tip on Rokfin. Even more importantly, I invite you to join us over on our Locals community, where I have posted the show notes for today's episode along with the links to watch the show live on YouTube, Rumble and Rokfin.

We’re continuing our investigation into FTX and Sam Bankman-Fried, a Rounding the News Special Investigation undertaken to bolster Mathew Crawford’s viral Substack article titled A Grand Unified Theory of the FTX Disaster. If you have not read it, do not delay any longer!

Who Is Peter Singer?

Peter Singer’s ancestry can allegedly be traced to “a line of scholars and rabbis” as far back as 1580.1 The family legacy is one of studying and speaking about psychology. His grandfather was David Ernst Oppenheim, an Austrian-Hungarian Jew who collaborated with none other than Sigmund Freud, along with another guy named Alfred Adler, as members of the Vienna Psychoanalytic Society.

According to Singer’s writing, Oppenheim perished of diabetes in a Nazi concentration camp in 1943.2 His widow and children moved to Melbourne, Australia, where Singer himself was born in 1946.

Singer attended Scotch College,3 a private school for boys that was recently described as “one of Australia’s richest schools.”4 He moved on to study law, history and philosophy at the University of Melbourne, graduating in 1969. He was swiftly admitted into the University of Oxford, completing a graduate degree in philosophy in 1971. He then taught at Oxford’s University College until 1973, when he travelled to New York University to work as a visiting assistant professor for a year.

Animal rights

While having lunch in Oxford’s Balliol College in 1970, Singer reportedly experienced a significant change of heart that led him to swear off meat.5

A quick note on Balliol College

Skipping past the anecdote itself (which you can watch in the video above), Balliol College is interesting. Among its graduates are former Prime Minister Boris Johnson and royalty from Norway and Japan, as well as the economist Adam Smith and the legendary Brave New World author Aldous Huxley.6789

It was also the alma mater of Alfred Milner, a British imperialist who led a secretive group of elite thinkers called the Round Table Group in the early 1900s.10 Described as a “movement” on Wikipedia and in other reputable sources,11 the Round Table is also framed as being the origin of a shadowy power structure functioning as a sort of "deep state" apparatus.12 Perhaps this is more a matter of institutional legacy, but I felt it was worth highlighting.

Anyway, the interaction Singer had with a classmate in a Balliol College lunchroom had quite the effect on him, and in 1975 he published Animal Liberation, described by the European Graduate School as having “greatly influenced the modern movements of animal welfare.”

Singer argues in particular that the fact of using animals for food is unjustifiable because it causes suffering disproportionate to the benefits humans derive from their consumption. According to Singer, it is, therefore, a moral obligation to refrain from eating animal flesh (vegetarianism) or even go as far as not consuming any of the products derived from the exploitation of animals (veganism).

Singer returned to Australia to teach as a senior lecturer at La Trobe University in 1975-1976.

Centre for Human Bioethics

Singer was hired in 1977 as a professor and Chair of the Department of Philosophy at Monash University, and served as the founding director of the school’s Centre for Human Bioethics in the early '80s.13 Co-founded with fellow bioethicist Helga Kuhse, the school claims to have been responsible for some of the very first published research on the topic of in-vitro fertilization (IVF) and topics related to reproductive health.14 According to the school:

Singer and Kuhse also developed influential critiques of a reliance on sanctity-of-human-life views by health professionals and lawmakers in justifying medical decisions at the beginning and end of life.

The two utilitarians seem to have been very much alike. The pair were criticized for their oddly enthusiastic argument in favour of infanticide, and their offence taken when others pointed out the “slippery slope” to Nazi-era extermination that normalizing such healthcare policies would invite.15

Nowadays, the renamed Monash Bioethics Centre runs research on “Reproductive Biomedicine and Technology”, “Values and Virtues in Healthcare” and “Infectious Disease Ethics” - all topics very much related to the current COVID-19 crisis.16 One ongoing study at the centre is titled "the legal and ethical issues in the inheritable genetic modification of humans."

Well, at least somebody’s asking the hard questions. But doesn’t this sound familiar? Is this not eerily similar in premise to the “gene drive” technology developed to eliminate malaria-carrying mosquitoes, which functions - for example - by inserting, activating or silencing genes that would be inherited by the next generation, rendering them sterile? You know, the genetic editing technology spearheaded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the National Institutes of Health and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with funding from Dustin Moskovitz’s Open Philanthropy?

How about this one?

The latter study is funded by the Australian Government through something called the Genomics Health Futures Mission, a $500 million allocation of a much larger ($20 billion) Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) announced in 2014.1718

Lobbying in favour of the fund was a coalition of Australian research institutes called the MRFF Action Group. Its membership included representatives from:19

Association of Australian Medical Research Institutes

AusBiotech

Australian Society for Medical Research

Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute

Burnet Institute

Cochlear

Group of Eight Deans of Medicine Committee

Group of Eight Universities Australia

Medical Deans Australia and New Zealand

Multiple Sclerosis Australia

New Zealand Research Australia

University of Melbourne

University of New South Wales

University of Queensland

Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute

Walter and Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research

It won’t be a shock to the Rounding the Earth audience that these organizations hold significant conflicts of interest, in no small part due to their funding partnerships with the pharmaceutical industry. Such a substantial government research funding program benefits these companies as well, assuming the various institutes agree to focus their time and energy on experiments and clinical trials of their choosing.

The Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute, for example, is funded by Abbott, AbbVie, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Eli Lilly, Fitbit, Johnson & Johnson, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtronic, Merck, National Institutes of Health (NIH), Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi and Takeda.20

Multiple Sclerosis Australia is funded by Biogen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Merck and Roche.21 The Burnet Institute receives funds from Gilead Sciences, developer of the highly-lethal remdesivir.22

AusBiotech is an industry association whose membership includes AbCellera (the Thiel-funded startup developing monoclonal antibodies with Eli Lilly), Amgen, AstraZeneca, Gingko Bioworks, Illumina, Johnson & Johnson, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Takeda, Vaxxas, and the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) - Australia’s pharmaceutical regulator.23

Meanwhile, the Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute is funded by investment giants BlackRock, Deustche Bank, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley - all huge shareholders in the world’s major pharmaceutical companies.24

But that’s not it. The centre is also running research on “infectious disease ethics” funded by Wellcome Trust, and an “ethical analysis” of gain-of-function research funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Another project titled “Building a sustainable capacity in dual-use bioethics” is looking at “the use of the products of biological research in warfare and bioterrorism.”

In summary, Singer’s legacy around Monash seems to be (at least in part) the continuation of the expansion of Australia’s robust pharmaceutical public-private partnership, with his own pseudo-eugenic flair. He served as co-director of Monash’s Institute for Ethics and Public Policy from 1992-1995.

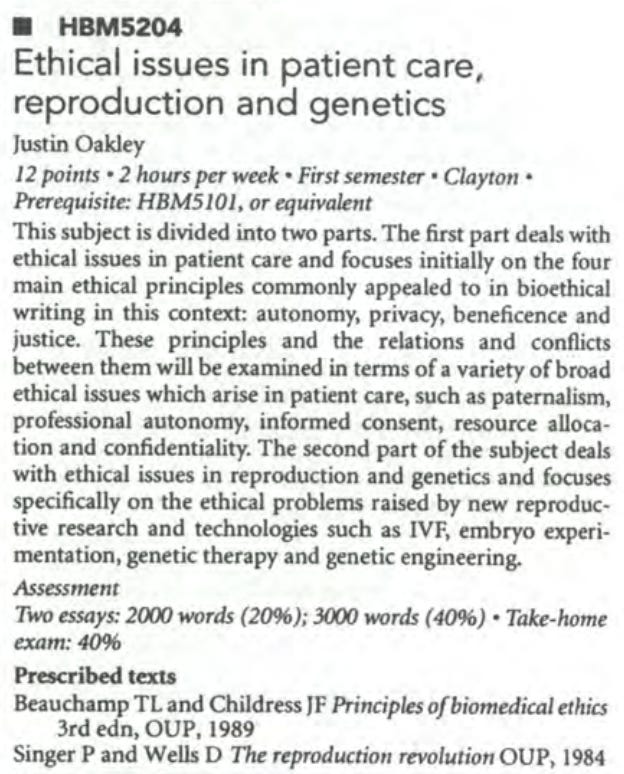

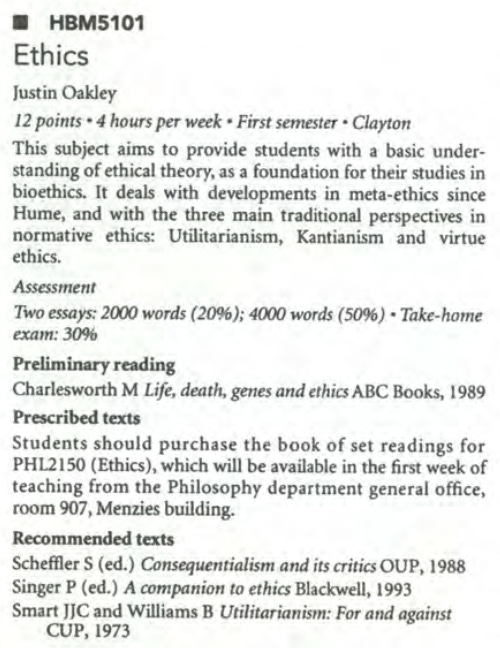

In a 1994 student handbook, Singer's texts are found as either recommended or prescribed for various courses.25 For example, his 1984 book titled The reproduction revolution is required reading for a class called “Ethical issues in patient care, reproduction and genetics.”

A companion to ethics, a 1993 book edited by Singer, is recommended for Monash’s course aptly titled “Ethics.”

For students taking the “Questions of life and death” course, Singer’s 1985 work titled Should the baby live? is fundamental.

Are you noticing a trend yet? Singer’s areas of interest are not only reminiscent of Nazi eugenics; in some ways, they seem to replicate them directly. These classes under his purview in the ‘90s explore “radical utilitarian” perspectives on issues of life an death in the context of healthcare and medical research, including “autonomy, privacy, beneficence, and justice” and “informed consent” specifically as it relates to “reproduction and genetics” with a special focus on “the ethical problems raised by new reproductive research and technologies such as IVF, embryo experimentation, genetic therapy and genetic engineering.”

As described by Whitney Webb in her Unlimited Hangout discussion on the topic shortly after the FTX collapse, Singer’s claim to infamy is his promotion of infanticide for utilitarian purposes.26 This is concerning given that the students of his institute were, in the '90s, engaging in "an examination of issues such as abortion, infanticide and euthanasia" to challenge the "ethical significance of the sanctity of life doctrine."

Global networking

Singer spent several years travelling around the world as a visiting scholar.

Institute for Society, Ethics & the Life Sciences/The Hastings Center

In 1979, he was a guest of New York’s Institute for Society, Ethics & the Life Sciences, a research centre founded nine years earlier to “address itself to the ethical, legal, and social questions arising from developments in the life sciences, especially in medicine, biology, and population,” specifically as pertains to the “growing possibilities of euthanasia, genetic engineering, behavior control, population control, and improved disease control”.27 The institute received early funding from the United Nations Fund for Population Activities (UNFPA) and the Rockefeller Foundation.28

It has since been renamed to The Hastings Center,29 where it continues to ask challenging ethical questions such as “whether vaccine mandates should be used to raise [COVID-19] vaccination rates among people who were vaccine-hesitant.”30 Just a few short years ago in 2016, the center describes its work figuring out how "to proceed with the testing and development of a technology called gene drives."31

When used in combination with CRISPR-Cas9 and other techniques, gene drives can alter, reduce, and even eliminate whole populations of organisms in the wild.

Interestingly, the section of the 2016 annual report titled Donors is... not there. Was this removed after the fact? If so, why? Apart from that year, oops, 2014 and 2015’s reports also scrapped the Donors page. CRAZY.

Nonetheless, I was able to find that the Hastings Center is funded since 2017 by our familiar friends at Amazon, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), Carnegie Corporation of New York, Facebook, Goldman Sachs, Harvard University, Johnson & Johnson, JPMorgan Chase, Merrill Lynch, Morgan Stanley, Novartis, Rockefeller University and Vanguard.3233

Perhaps even more notable is one of the fellows of the Hastings Center: none other than Christine Grady, head of the Department of Bioethics at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center and wife of one Anthony Fauci.34

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars

Also in 1979, Singer became a fellow of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars, a “quasi-government entity and think tank which conducts research to inform public policy” for the United States government.35 In essence, it is a government owned and run think tank whose donors include the world's most powerful corporations, military contractors, foreign governments and other private interests. Some of the most notable include:3637383940

Amazon

Atlantic Council

Eli Lilly

European Commission

Facebook

Gilead Sciences

Goldman Sachs

Google

Government of Canada

Harvard University

Johns Hopkins University

Johnson & Johnson

Los Alamos National Laboratory

Merck

National Geographic Society

Open Philanthropy

Open Society Foundations

Pfizer

Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA)

Raytheon

Ripple

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Rockefeller Brothers Fund

Silicon Valley Community Foundation

Stanford University

United Nations Development Programme (UNDP)

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO)

United Nations Foundation

United States Agency for International Development (USAID)

United States Department of State

William and Flora Hewlett Foundation

World Wildlife Fund (WWF)

Zoom

From 1981 through 2003, Singer floated through the University of British Columbia (UBC), University of Colorado Boulder, University of California Irvine, Sapienza University of Rome, University of Canterbury, and the University of Girona, with quick one-off lectures and recognitions at Harvard’s John F. Kennedy School of Government, Stanford University, Yale University, Brooklyn College, World Technology Network, Wesleyan University, International Academy of Humanism, University of Pennsylvania, University of Bucharest, and several others.

In 1992, Singer became the President of the International Association of Bioethics, where he stayed active on the Board of Directors until at least 1999.

University Center for Human Values

In 1999, Singer was appointed as Ira W. DeCamp Professor of Bioethics in the University Center for Human Values at Princeton University. Describing Singer in The New Yorker as "the dangerous philosopher," writer Michael Specter provided some fairly understandable reasons for people to be concerned with Princeton's hiring choice. He pointed out that Singer had previously asserted "that it might be more compassionate to carry out medical experiments on hopelessly disabled, unconscious orphans than on perfectly healthy rats."41

The UCHV itself isn’t without red flags in this regard as well - Mark F. Rockefeller, son of Nelson Rockefeller, is a member of the advisory council.42 Mark's uncle, Laurance Rockefeller, was the founding donor to the school nine years prior to Singer's appointment.43

Project Syndicate

Starting in 2001, Singer began contributing to a media program called Project Syndicate, which “publishes and syndicates commentary and analysis on a variety of global topics.” Put another way, the service solicits and disseminates opinion pieces (op-eds) from subject matter experts that can then be used by other media organizations in their own so-called “reporting.”

A 2017 article for the platform co-authored by Singer is titled “Rethinking the Population Control Taboo.”44 Responding to comments made by French President Emmanuel Macron, Singer wrote:

Macron violated a taboo that has been in place since the International Conference on Population and Development, held under the auspices of the UN in Cairo in 1994. The conference adopted a Programme of Action that rejected a demographically driven approach to population policies, and instead focused on meeting the reproductive-health needs of individuals, especially women. Population targets were out; rights were in. …

One searches in vain for any suggestion that it might be appropriate, or wise, to seek to influence the number of children women choose to have, let alone to consider whether continued rapid population growth in some regions may be incompatible with the goal of sustainable development.

Sustainable Development is the institutional status quo. If Peter Singer holds any sway at all, that reaffirms the notion that there is at least some motivation to limit or reduce the global population in the academic-public policy circles.

It’s also relevant to note the ideological nature of Project Syndicate, which can in part be identified by its funders. Those, unsurprisingly, include:

Children's Investment Fund Foundation (CIFF)

European Climate Foundation

European Journalism Centre

Google Digital News Initiative

Mastercard Foundation

McKinsey Global Initiative

Nature Conservancy

Open Society Foundations

Sustainable Development Solutions Network

Recall that CIFF is the former employer of British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak, and a major funder of the Together Trial that manipulated institutional perception of ivermectin in treating COVID-19. More on that in my previous report on the topic:

Between November 2012 and November 2022, Project Syndicate also received four grants worth $6,929,601 from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation for “Global Health and Development Public Awareness and Analysis.”45464748

Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics

In 2005, Singer returned to the University of Melbourne to take up a position at the Centre for Applied Philosophy and Public Ethics. That same year, he was named on TIME’s list of 100 Most Influential People.49

Effective Altruism

At this point, we have established that Peter Singer has had a long, storied career through which he has influenced the minds and hearts of many, many people worldwide (for better or worse). But how does this tie in to our story of “effective altruism”?

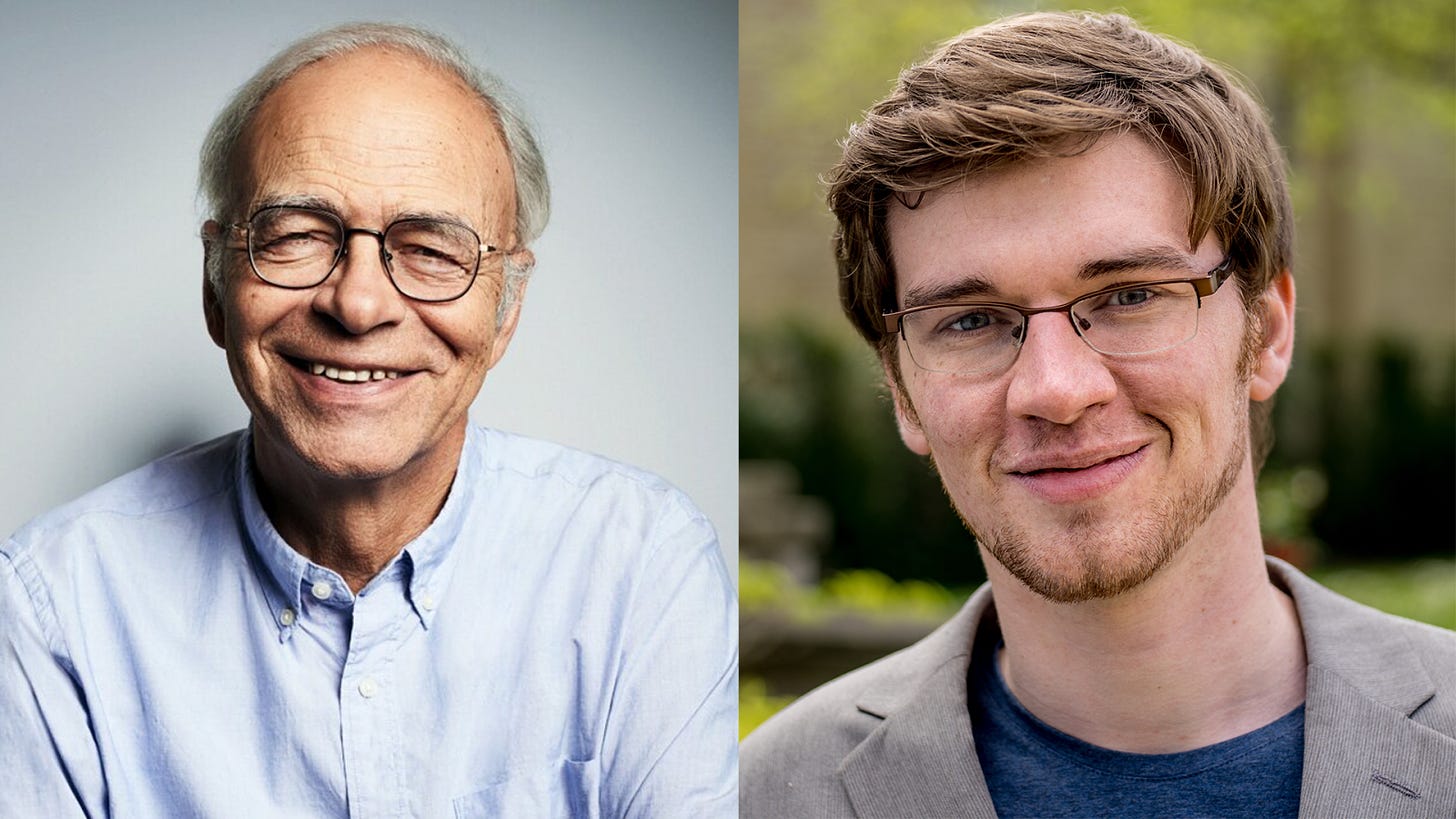

William MacAskill, described as the founder of the modern EA movement, himself cites Singer’s 1972 essay titled Famine, Affluence, and Morality as being the spark that lit his altruistic flame. As recounted in The New Yorker:50

Singer, prompted by widespread and eradicable hunger in what’s now Bangladesh, proposed a simple thought experiment: if you stroll by a child drowning in a shallow pond, presumably you don’t worry too much about soiling your clothes before you wade in to help; given the irrelevance of the child’s location—in an actual pond nearby or in a metaphorical pond six thousand miles away—devoting resources to superfluous goods is tantamount to allowing a child to drown for the sake of a dry cleaner’s bill. For about four decades, Singer’s essay was assigned predominantly as a philosophical exercise: his moral theory was so onerous that it had to rest on a shaky foundation, and bright students were instructed to identify the flaws that might absolve us of its demands. MacAskill, however, could find nothing wrong with it.

“By the time MacAskill was a graduate student in philosophy, at Oxford, Singer’s insight had become the organizing principle of his life.” In fact, when MacAskill first launched Giving What We Can, he convinced Singer to join on as a signatory. Poetically, the organization was launched at Balliol College, where Singer first had his mind blown in the direction of becoming the world’s most impactful animal rights activist.

As we’ve seen, of course, MacAskill was not the only “effective altruist” emerging at the time. Holden Karnofsky and Elie Hassenfeld formed GiveWell shortly thereafter, and they also credited Singer as the source of their inspiration. Singer became a member of GiveWell’s advisory board at some point, by the way.

Then, there’s Matt Wage, a student of Singer’s at Princeton who took a job at Jane Street Capital to get rich enough to then give it all away. We’ll finally be coming back for Jane Street next week.

The New Yorker seems to be right: “Insofar as there was a common ancestor, it was Peter Singer.”

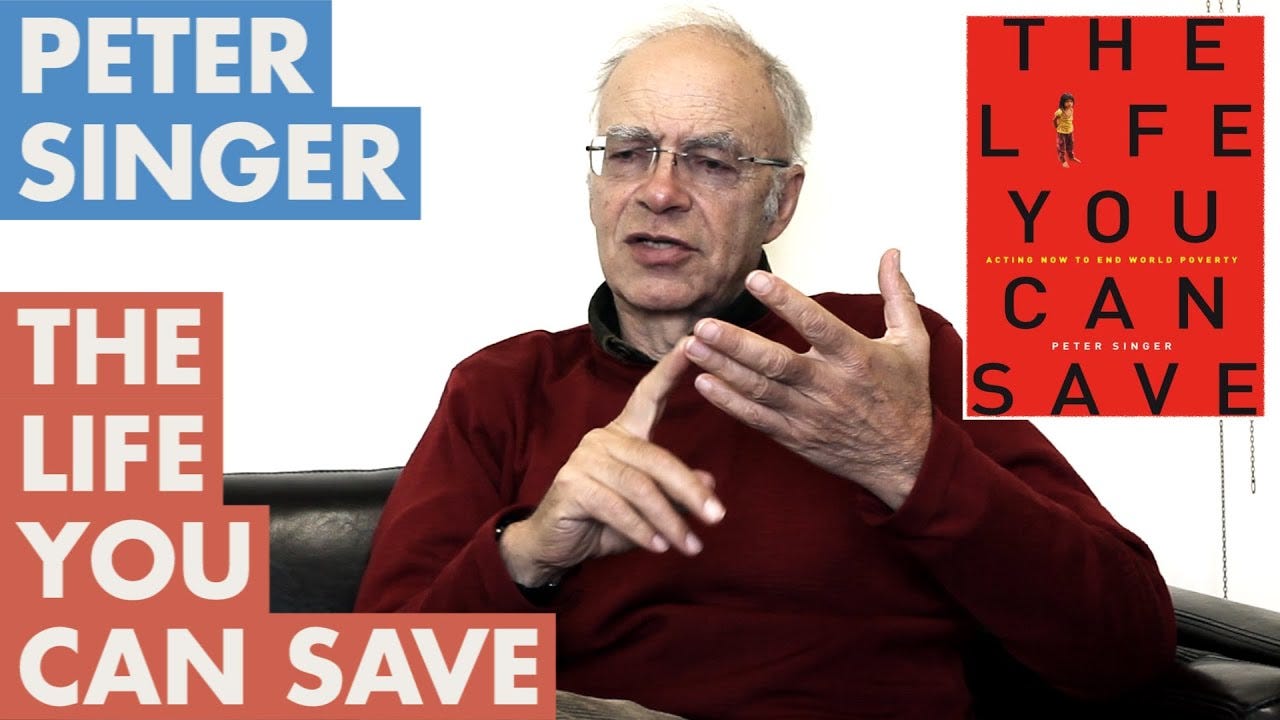

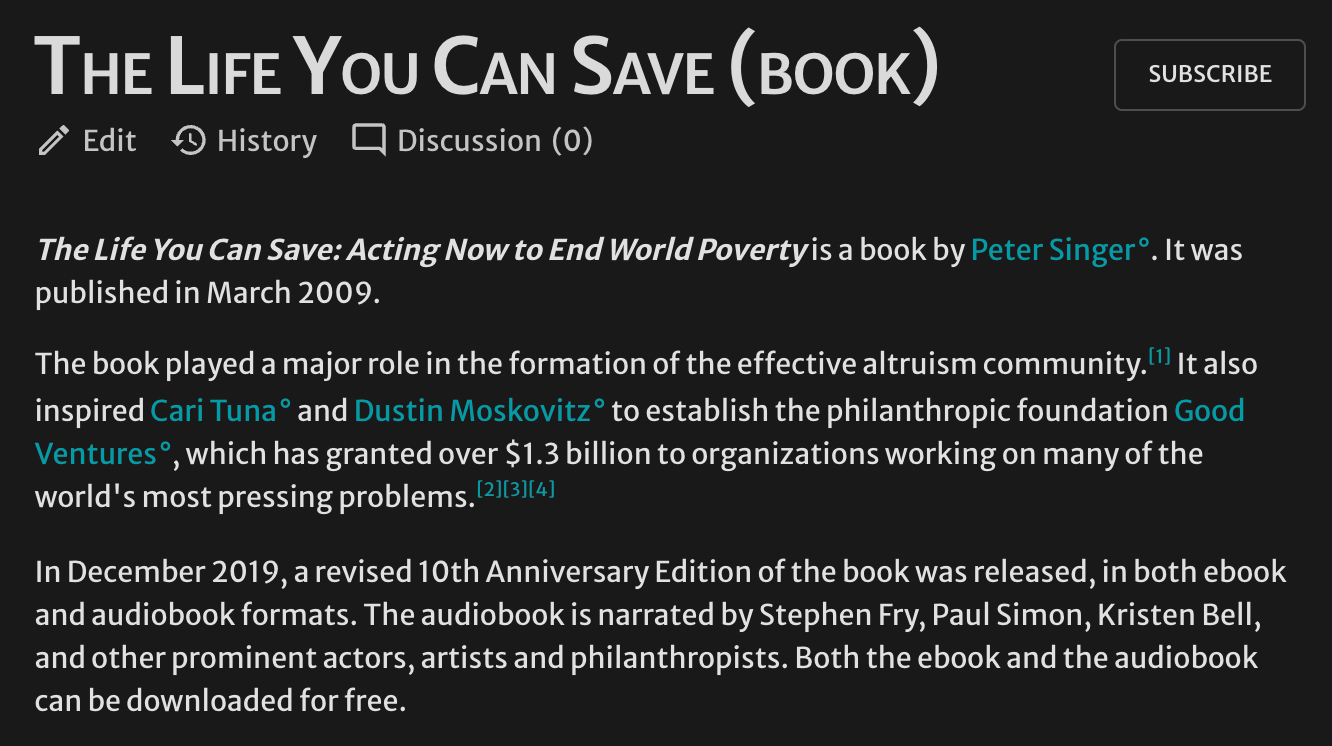

The Life You Can Save

In 2009, Singer published a book titled The Life You Can Save: Acting Now to End World Poverty.51 His argument centers around effective altruism, asserting that "if we can provide immense benefit to someone at minimal cost to ourselves, we should do so."52

It was this book that sold Cari Tuna on effective altruism. From the official EA Forum:53

At least according to Vox, the book is described as having played “a powerful role in birthing the effective altruist movement,” which “inspired major donors to give more effectively.”54 From the article:

I first read the book in 2011, when I was 17, and found it bracingly straightforward: People are dying, we know how to fix that, we just have to donate money and tell everyone else to do so as well. And while as an adult it’s obvious that many of the details of how to fix the world are more complicated than that, the simple core remains, and speaks loudly and clearly to the sort of people who become effective altruists: The world could be better, and you can make it that way.

In 2013, the organization was registered as a charity in the United States and started engaging directly on the modern effective altruism platform. The Life You Can Save’s website lists both Peter Singer and William MacAskill in prominent positions, presenting them as effectively co-founders of the EA movement.

The organization, like pretty much every EA venture, is all about hoisting up their favourite charitable organizations. For The Life You Can Save, they have chosen to push on behalf of many that we’ve come across in our investigation so far:55

Against Malaria Foundation

Carbon180

Clean Air Task Force

Development Media International

Equalize Health

Evergreen Collective

Evidence Action

Fistula Foundation

GiveDirectly

Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition

Helen Keller International

Innovations for Poverty Action

Iodine Global Network

Living Goods

Malaria Consortium

New Incentives

Oxfam

Population Services International (PSI)

Schistosomiasis Control Initiative

Most partners of the organization will also be very familiar by this point:

Double Up Drive

The Funding Network

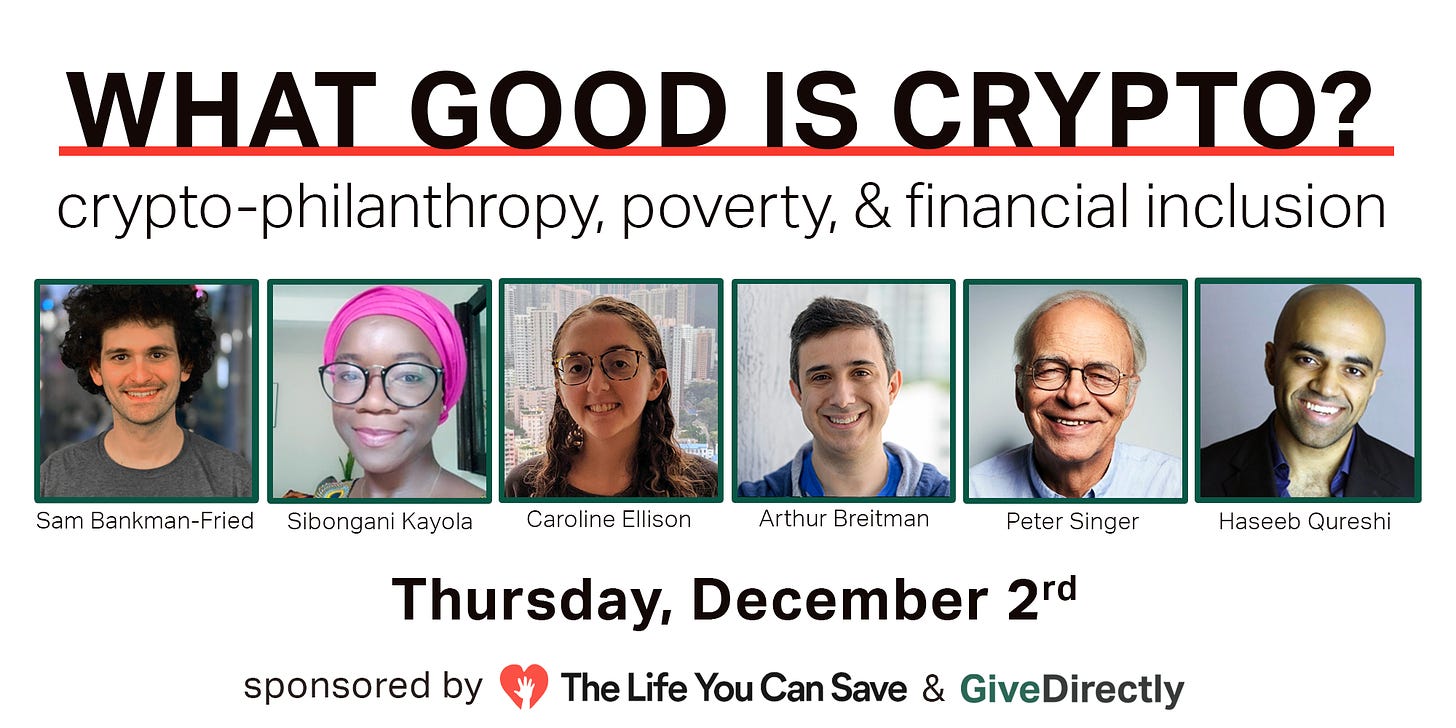

In 2021, the organization launched a new cryptocurrency fundraising capability which they kicked off in style: “we partnered with our recommended charity GiveDirectly to co-host a virtual panel and fundraiser that featured FTX’s Sam Bankman-Fried and other leading figures in crypto philanthropy and raised over $1 million in support for GiveDirectly.”56

The Godfather of EA

Singer has been all over the world, laying seeds for what would become Effective Altruism. But along the way, he engaged in thorough academic research, discussion and debate about topic highly relevant to the COVID-19 crisis we have all just been through, including euthanasia, infectious disease ethics, the sanctity of life, bodily autonomy, medical privacy, biological warfare, genetic editing… frankly, eugenics.

It’s no wonder so many of his proteges have spun on a dime in their own lives to focus on Singer’s areas of interest - though I admit, researching and investigating this “official narrative” leaves me feeling like I’m being told a convenient tale. Without a shadow of a doubt, there’s more to this story than currently faces the public.

There’s so much more to learn about Peter Singer. Here’s just a short list of known affiliations that I didn’t have time to dig into:

Academics Stand Against Poverty

Agriculture Victoria Animal Welfare Advisory Committee

American Philosophical Association

Animal Liberation

Animal Rights International

Australian Academy of the Humanities

Australian Academy of the Social Sciences

Australian and New Zealand Federation of Animal Societies

Australian Humanist Association

Brooklyn College

Centre for Ethics, Philosophy and Public Affairs (CEPPA)

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (CSIRO)

Farm and Food Society

Freedom from Religion Foundation

Fulbright Program

Giordano Bruni Stiftung

Global Happiness Organization

Gottlieb Duttweiler Institute

The Great Ape Project

International Academy of Humanism

John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard University

Linacre College at the University of Oxford

National and Kapodistrian University of Athens

Oxfam America Leadership Council

Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics

Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals

University of Bucharest

University of Pennsylvania

Wesleyan University

World Council of Religious Leaders

World Technology Network

…as well as leadership and advisory duties at academic journals such as:

Australasian Journal of Philosophy

Bioethics

Ethics

International Journal for the Study of Animal Problems

Journal of Applied Philosophy

Journal of Controversial Ideas

Journal of Medicine and Philosophy

Philosophy and Geography

Philosophy of Management

Reason in Practice

I hope I’ve thoroughly demonstrated Singer’s influence on this area of academia, if only in volume. Next week, we will return for our fifth and final instalment in this impromptu “special investigation” into Effective Altruism: Sam Bankman-Fried and the FTX Phantom.

If you’ve enjoyed the show and have been watching live, please drop us a Rumble Rant or a tip on Rokfin.

Most importantly, before you leave, go sign up as a member of our Locals community at www.RoundingtheEarth.locals.com. There, we are hosting weekly “insider” discussions about topics we’re not yet prepared to go public with, but bear discussing nonetheless.

If you have not read Mathew’s viral article, on FTX and the Grand Unified Theory of the associated disaster, it’s time you do so, as I consider this Rounding the News special investigation to be supplementary to his piece.

You can even snag yourself a free month of premium support on Locals using the promo code included on the pinned comment, after which you can choose to pay as little as $5/month to keep us going and gain access to behind-the-main-scenes discussions that we’re keeping within our more intimate community.

I have been Liam Sturgess, and you can find me at www.LiamSturgess.com, or on Twitter @TheLiamSturgess. See you next week!

Henderson, R. (2021, July 30). How philosopher Peter Singer came to appreciate billionaires. Australian Financial Review. https://archive.vn/xZQcA

Singer, P. (2003). Pushing Time Away. Open Road Media.

Peter Singer. The European Graduate School. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221215002215/https://egs.edu/biography/peter-singer/

Schneiders, B., & Millar, R. (2021, June 17). How Australia’s top private schools are growing richer. The Sydney Morning Herald. https://archive.vn/iuTBb

voicesfromoxfordUK. (2013, October 1). The Ethics of Food: The Making of a Vegetarian and Professor of Bioethics - Peter Singer. YouTube. https://web.archive.org/web/20221009051419/

Balliol’s fourth Prime Minister. (2019, July 24). Balliol College, University of Oxford. https://web.archive.org/web/20220710102915/https://www.balliol.ox.ac.uk/news/2019/july/balliols-fourth-prime-minister

Forr, G., & Allkunne. (2022, October 14). Harald 5. Store Norske Leksikon. https://web.archive.org/web/20220921200233/https://snl.no/Harald_5.

College History. Balliol Archives. Retrieved December 23, 2012, from https://archive.vn/uCY7

New building named after Aldous Huxley. (2021, December 14). Balliol College, University of Oxford. https://web.archive.org/web/20220705033531/https://www.balliol.ox.ac.uk/news/2021/december/new-building-named-after-aldous-huxley

Alfred Milner. South African History Online. Retrieved October 1, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221001142343/https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/alfred-milner

Bosco, A. (2017). The Round Table Movement and the Fall of the “Second” British Empire (1909-1919). Cambridge Scholars Publishing. https://web.archive.org/web/20220206164511/https://www.cambridgescholars.com/resources/pdfs/978-1-4438-9971-0-sample.pdf

Ehret, M. Origins of the Deep State. Highlander; Canadian Patriot. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20211021190451/https://highlanderjuan.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Matthew-Ehret-Origins-of-the-Deep-State-Parts-1-3-a.pdf

Peter Singer CV. (2022). Peter Singer. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5950e846c534a573ac225a22/t/636b84149adbea3c492d80ee/1667990550785/CV+09+November+2022.pdf

About. Monash Bioethics Centre. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://www.monash.edu/arts/bioethics/about

Fairbairn, G. J. (1988). Kuhse, Singer and Slippery Slopes. Journal of Medical Ethics, 14(3), 132–147. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27716714

Research. Monash Bioethics Centre. Retrieved November 24, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221124160019/https://www.monash.edu/arts/bioethics/research

Medical Research Future Fund’s Genomics Health Futures Mission - National Consultation on the Roadmap, Implementation Plan and Summary of Recommendations from the Scientific Strategy Committee Report. (2021, April 23). Australian Government Department of Health - Citizen Space. https://web.archive.org/web/20221024230455/https://consultations.health.gov.au/health-economics-and-research-division/mrff-ghfm/

Funding changes for Medical Research Future Fund. (2014, December 16). MS Australia. https://web.archive.org/web/20221108042512/https://www.msaustralia.org.au/news/funding-changes-medical-research-future-fund/

Butcher, A., & Beswick, L. (2014, August 31). New MRFF Action Group advocates for the most important initiative in Australian medical research in generations. AAMRI. https://web.archive.org/web/20221025053004/https://www.aamri.org.au/news-events/aamri-news/new-mrff-action-group-advocates-for-the-most-important-initiative-in-australian-medical-research-in-generations/

2021 Impact Report. Baker Institute. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://baker.edu.au/who-we-are/institute/corporate-reports

Industry. MS Australia. Retrieved November 12, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221112095438/https://www.msaustralia.org.au/about-us/partnerships/industry/

Padbury, M., & Crabb, B. Annual Report 2021. Burnet Institute. Retrieved December 14, 2022, from https://www.burnet.edu.au/system/annual_report/file/32/2021-BurnetInstitute-AnnualReport.pdf

Member Directory. AusBiotech Ltd. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221215061828/https://www.ausbiotech.org/biotechnology-industry/member-directory

Annual Reports. The Victor Chang Cardiac Research Institute. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://www.victorchang.edu.au/about-us/annual-reports

Arts graduate handbook 1994. (1994). Monash University. https://web.archive.org/web/20221215185649/https://www.monash.edu/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/2812235/Arts_Graduate_Handbook_1994-compressed.pdf

Unlimited Hangout. (2022, November 22). The Network Behind FTX. Rokfin. https://rokfin.com/post/109744

Callahan, D. (1971). Profile: Institute of Society, Ethics and the Life Sciences. BioScience, 21(13), 735–737. https://www.jstor.org/stable/1295928

Callahan, D., & Watson, J. D. (1976, December 30). Memorandum to the Board of Directors from Daniel Callahan. CSHL Archives Repository; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Archives. http://libgallery.cshl.edu/items/show/39559

Institute of Medicine (US) Council on Health Care Technology, C. Goodman (Ed.)(1988). Hastings Center. National Academies Press (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218427/

Solomon, M. Z. Annual Report 2021: Deciding Together. The Hastings Center. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221215223532/https://www.thehastingscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2021-annual-report-online.pdf

Solomon, M. Z. 2016 Annual Report: Listen. Understand. Act. The Hastings Center. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221215225757/https://www.thehastingscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2016-Annual-Report.pdf

Solomon, M. Z. Annual Report 2020: Ethics for a World in Crisis. The Hastings Center. Retrieved November 1, 2021, from https://web.archive.org/web/20211101034223/https://www.thehastingscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2020-annual-report-online.pdf

Solomon, M. Z. Annual Report 2018: Working for Human Values in Policy and Practice. The Hastings Center. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221215225747/https://www.thehastingscenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2018-annual-report-FINAL.pdf

Grady, C. (2015, September 21). Clinical Trials. The Hastings Center. https://www.thehastingscenter.org/briefingbook/clinical-trials/

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. USAGov. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221216000101/https://www.usa.gov/federal-agencies/woodrow-wilson-international-center-for-scholars

Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. InfluenceWatch. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://www.influencewatch.org/non-profit/woodrow-wilson-international-center-for-scholars/

2021 Donors. Wilson Center. Retrieved August 8, 2022, from https://archive.vn/L0GeY

2020 Donors. Wilson Center. Retrieved April 30, 2022, from https://archive.vn/QAoVo

2019 Donors. Wilson Center. Retrieved August 9, 2020, from https://web.archive.org/web/20200809135351/https://www.wilsoncenter.org/2019-donors

The Wilson Center donations received. Vipul Naik. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://archive.vn/AriBf

Specter, M. (1999, August 29). The Dangerous Philosopher. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/1999/09/06/the-dangerous-philosopher

Advisory Council. University Center for Human Values. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://uchv.princeton.edu/people/advisory-council

About the Center. University Center for Human Values. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://uchv.princeton.edu/about-the-center

Singer, P., & Kissling, F. (2017, August 4). Rethinking the Population Taboo. Project Syndicate. https://archive.vn/thCjz

The Project Syndicate, o.p.s. (2012, November). Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. https://archive.vn/kz9Cw

The Project Syndicate, o.p.s. (2016, October). Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. https://web.archive.org/web/20211124043208/https://www.gatesfoundation.org/about/committed-grants/2016/10/opp1160642

The Project Syndicate, o.p.s. (2019, October). Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. https://web.archive.org/web/20220120213417/https://www.gatesfoundation.org/about/committed-grants/2019/10/opp1216840

The Project Syndicate, o.p.s. (2022, November). Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. https://archive.vn/Rdn2n

Peter Singer. HarperCollins Speakers Bureau. Retrieved December 15, 2022, from https://www.harpercollinsspeakersbureau.com/speaker/peter-singer/

Nast, C. (2022, August 8). The Reluctant Prophet of Effective Altruism. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2022/08/15/the-reluctant-prophet-of-effective-altruism

About Me. Peter Singer. Retrieved February 1, 2022, from https://archive.vn/tmKZV

Our story. The Life You Can Save. Retrieved August 17, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20220817002433/https://www.thelifeyoucansave.org/our-story/

The Life You Can Save (book). EA Forum. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/topics/the-life-you-can-save-book

Piper, K. (2020, December 11). “The world’s problems overwhelmed me. This book empowered me.” Vox. https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/21561606/peter-singer-life-you-can-save-effective-altruism

Money Moved 2021 - By Charity. The Life You Can Save. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://web.archive.org/web/20221216024430/https://www.thelifeyoucansave.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/tlycs_ar21_moneymoved_bycharity.pdf

2021 Annual Report. The Life You Can Save. Retrieved December 16, 2022, from https://archive.vn/EsLKG