Public-Private Cybersecurity

Deep dive into "Volt Typhoon" and what it shows about narrative control

Microsoft and intelligence agencies warn of Chinese cyberattack

On Wednesday, May 24, a rather interesting story came to my attention through two sources that are not usual bedfellows. First, I received a notification from Truth Social, followed by a New York Times news alert shared by a member of a Bitcoin discussion group that I’m in. To paraphrase, that member noted, “if the NYT is trying to get me to pay attention to this, something smells fishy.”

Let’s explore this story and see what we can glean.

Microsoft issues alert

Authored by Microsoft Threat Intelligence, the report describes a hacking of networks supporting “critical infrastructure organizations in the United States.”1 The source of the hack is named as Volt Typhoon, which Microsoft describes as a “a state-sponsored actor based in China that typically focuses on espionage and information gathering.”

In their view, Microsoft “assesses with moderate confidence that this Volt Typhoon campaign is pursuing development of capabilities that could disrupt critical communications infrastructure between the United States and Asia region during future crises.”

Now, I’m not the tech wizard that will be required to interpret the nitty-gritty of the report itself. For that, I’ll turn to my buddy Gabriel at

. I think it’s fair to say, however, that the headlines this story has generated are keen to frame this network infiltration as a direct attack on the United States from a group with the backing of the Chinese government. Look no further than CNBC's offering:2Beyond simple due diligence on Microsoft’s part, this appears to be something that has alarmed the network of intelligence agencies known as the Five Eyes. The coalition of agencies published their own concurrent report titled “People's Republic of China State-Sponsored Cyber Actor Living off the Land to Evade Detection” in which they elaborate on the national security implications of Microsoft’s discovery, though the report largely focuses on a set of instructions for how to identify and log potential malicious activity.3 They also caution against assuming any particular event is malicious, which is quite a bit of a different tone than CNBC strikes.

The agencies who signed off on the “joint Cybersecurity Advisory” include:

National Security Agency (NSA)

Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)

Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)

Australian Cyber Security Centre (ACSC)

Canadian Centre for Cyber Security (CCCS)

New Zealand National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC-NZ)

United Kingdom National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC-UK)

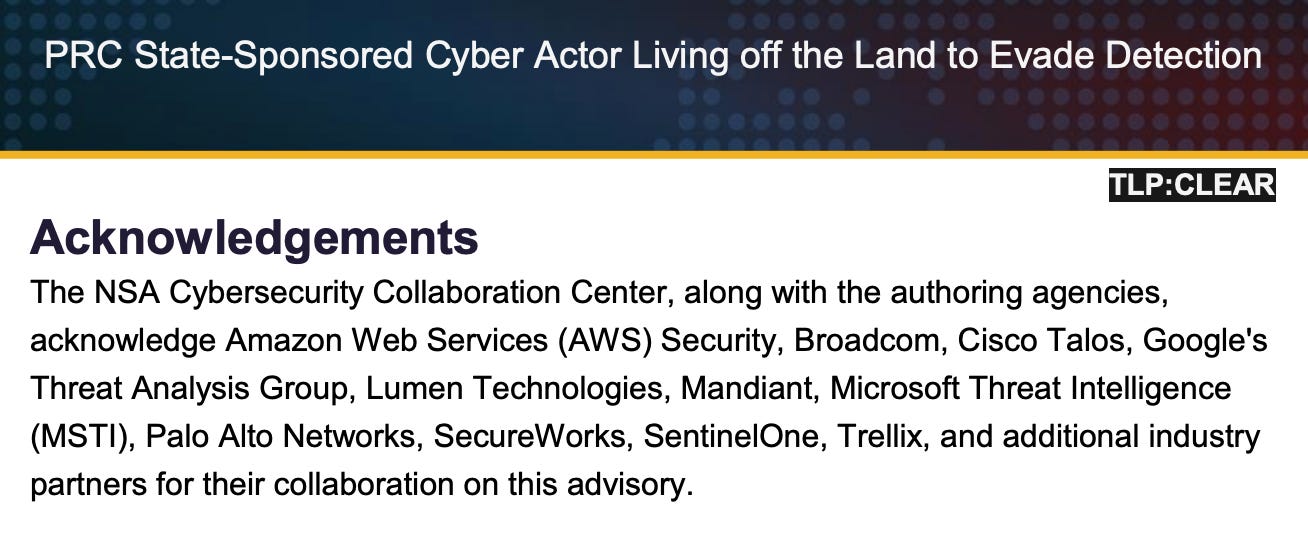

What I find immediately interesting about this report is that it is, in fact, a collaboration between the public and private sectors. Right off the bat, the report states:

“Private sector partners have identified that this activity affects networks across U.S. critical infrastructure sectors, and the authoring agencies believe the actor could apply the same techniques against these and other sectors worldwide.”

Who are those private sector partners? They are listed on page 22 under “Acknowledgements”:

Amazon Web Services (AWS) Security

Broadcom

Cisco Talos

Google's Threat Analysis Group

Lumen Technologies

Mandiant

Microsoft Threat Intelligence (MSTI)

Palo Alto Networks

SecureWorks

SentinelOne

Trellix

“…and additional industry partners.”

This is not the first time in recent history that I have approached a “cyberattack” story with a skeptical eye. Back in March, I covered the so-called “Vulkan Files” which accused a Russian “state-sponsored” tech firm of engaging in cyber warfare and disinformation campaigns on behalf of the Kremlin.

Confession Through Projection

My focus is generally on the flow of money and influence. As such, I examined the parties involved to try to identify conflicts of interest in the narrative, and found them everywhere. The media outlets and NGOs that produced the Vulkan Files were heavily funded by several different agencies of the United States government, with an explicit focus on shaping the narrative around foreign affairs and human rights issues.

Then came the flagship article from The Guardian, which tapped a tech company called Mandiant for comment. Mandiant is a subsidiary of Google, and it appears alongside its parent company’s Threat Analysis Group on the above list of companies that contributed to the Five Eyes report from this week. As I concluded in my report on the Vulkan Files, this is important because of Google’s longstanding collaborative relationship with governments in the United States and around the world, occasionally blurring the lines between military and commercial activities on projects like Google Earth.

What about the rest of the “private” companies who contributed to the report? To what extent do the private and public sector collaborate on matters of national cybersecurity?

Before we explore that question further, let’s first address the group blamed for the hack.

Volt Typhoon

Volt Typhoon is a codename used by Microsoft and the Five Eyes to describe a “People’s Republic of China (PRC) state-sponsored cyber actor”. According to Microsoft, the group “has been active since mid-2021 and has targeted critical infrastructure organizations in Guam and elsewhere in the United States. In this campaign, the affected organizations span the communications, manufacturing, utility, transportation, construction, maritime, government, information technology, and education sectors.”

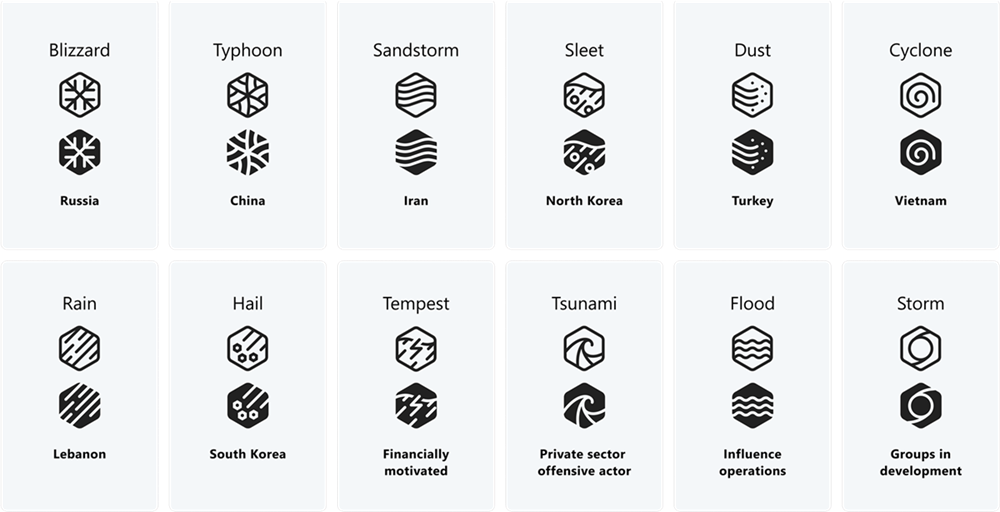

Importantly, the name “Volt Typhoon” was made up by Microsoft, rather than selected by the hacking group itself. Microsoft’s report links to an explainer on how the company’s naming taxonomy works:

There are two parts to the naming scheme. The second name, or the “family name”, is decided based on what kind of entity is being described. Those could be nation states, financially motivated actors, private sector entities, influence operations or so-called “groups in development.”4

The page helpfully uses China as an example:

“In our new taxonomy, a weather event or family name represents one of the above categories. In the case of nation-state actors, we have assigned a family name to a country of origin tied to attribution, like Typhoon indicates origin or attribution to China.”

Other possible nations of origin listed are Iran, Lebanon, North Korea, Russia, South Korea, Turkey and Vietnam. You know, the bad guys!5

As for the first half of the name, “[t]hreat actors within the same weather family are given an adjective to distinguish actor groups that have distinct TTPs, infrastructure, objectives, or other identified patterns.”6 Hence, Volt Typhoon.

In other words, Volt Typhoon is less of a group and more of a theory. It’s a codename used to label a threat actor, whether or not sufficient intelligence exists to formally assert the nature of its organization or participants. Same goes for the logo I found on Microsoft’s website and shared above.

To further complicate matters, other organizations use entirely different codenames to describe the hacking group. Secureworks, a company which we will revisit in a moment, uses the name Bronze Silhouette in their own statement released on Wednesday.7

The only thing that Microsoft or the Five Eyes actually assert in this regard is that Volt Typhoon is, as a matter of fact, sponsored by the People’s Republic of China (though Secureworks is a bit more direct).

What this means is that independent research into Volt Typhoon is not possible in the way I would usually approach it. Nonetheless, this is a task that Reuters took on in an article on Thursday titled “Factbox: What is Volt Typhoon, the alleged China-backed hacking group?”8

Refreshingly, the article starts by pointing out that “nearly every country in the world uses hackers to gather intelligence,” with the United States and Russia in particular commanding “large stables of such groups.” This gets out of the way my main point of contention with the reporting I usually see, which seems to go out of the way to paint these covert cyber activities as being something that only “the bad guys” do.

Sabotage

But this veneer of objectivity quickly shifts into speculation over intentions and potential plans behind the hacking operation, most immediately tying it to the “escalating tensions between China and the United States over Taiwan.” After all, they argue, “any conflict between those two countries would almost certainly involve cyberattacks across the Pacific.”

While the article acknowledges that Microsoft was only moderately confident it knew what it was talking about, it is all to happy to endorse the unsubstantiated accusation that China was using this campaign in order to prepare for a more direct cyberattack.

The aforementioned Secureworks is a subsidiary of Dell Technologies. Its Wednesday report on “Bronze Silhouette” describes how the company had previously encountered intrusions from the group in June 2021, September 2021 and June 2022. They concluded that the group “likely operates on behalf the PRC,” opining that “the targeting of U.S. government and defense organizations for intelligence gain” was consistent with China’s priorities.

Marc Burnard, the company’s “lead China researcher,” suggested to Reuters that China “may well be positioning itself for disruption”. Cisco’s contribution to the article is that “it has seen disturbing evidence that Volt Typhoon was readying itself for something dangerous.”

China escalations narrative

The above headline strikes right to the heart of the matter: China could really mess up peoples’ days in ways far worse than just having their data stolen.

However, in a prime example of “blink-and-you’ll-miss-it” narrative shifting, this article used to read something entirely different. I snapped a screenshot of that headline from the article as it was at 3:23PM Pacific Time on May 25, 2023. But if you had read the article at 4:43AM this morning, you would have seen this:

Relegated to near the bottom of that particular article is the official rebuttal from Chinese spokesperson Mao Ning, who described “the joint warning issued by the United States and its allies a ‘collective disinformation campaign.’”9

In the new version, the focus shifts entirely to front-loaded warnings from the United States Department of State that “China was capable of launching cyber attacks against critical infrastructure, including oil and gas pipelines and rail systems.”10 Ning’s reply is still there, but it’s far less visible and certainly will result in fewer readers even knowing China had articulated a reply.

One URL, two stories. It’s sort of crazy how this works.

But now that the basic story has been set, speculation becomes fact through re-reporting over the course of the day, like a game of telephone. The result is the seeding of a narrative that China has been caught hacking into critical U.S. infrastructure, through which they have planted seeds for an increasingly-likely cyberattack that will cripple communications, travel, or the economy in some explosive form.

As I always note, I have no doubt that China would benefit greatly from such an attack, and likely are working towards such a thing. But the notion that this story serves as proof of such allegations remains speculation, based on everything I’ve seen so far.

Private entities behind the report

Another thing that will surely be lost on most people casually consuming this news is the fact that the report was not generated independently and then substantiated by a separate group. For example, one might assume that Microsoft (a private corporation) led the charge on breaking the news, which an appreciative intelligence community (a coalition of public agencies) validated with their subsequent statement. The same could work vice versa, where the intelligence community identified what it saw as a potential threat in its realm of international operations, then hired a private corporation in order to apply their technical expertise to fill out the body of intelligence.

In fact, neither of those are correct. Instead, the public and private sectors worked collaboratively to investigate and respond to this incident, acting in tandem in their communications and recommendations. As previously mentioned, Microsoft’s report points directly to the Five Eyes’ own advisory, which itself was generated in partnership with half a dozen big tech giants.

NSA Cybersecurity Collaboration Center

The Five Eyes report was generated through the National Security Agency’s Cybersecurity Collaboration Center, which was established in 2020 “to engage with industry partners, share information on nation state cyber threats, and develop strategies to counter these threats.”11 It “focuses on bidirectional information sharing” between the NSA and the more than 250 participating companies.12

The center was conceived in 2019 by Anne Neuberger, former head of the NSA’s Cybersecurity Directorate and current Deputy National Security Advisor in the White House.

A June 2021 article from Reuters noted that the center was opened “after a series of high-profile hacks over the last year, including a massive cyberattack that penetrated numerous federal agencies and another that crippled a major U.S. gas pipeline.”13 The Cybersecurity Collaboration Center is so important, it seems, as a mechanism to skirt “legal restrictions that prevent the NSA and other federal spy agencies from collecting data on domestic computer networks.”

Which companies are part of this public-private partnership, you might ask? Tough luck. “The agency declined to identify companies participating in the center and did not commit to naming them in the future.” Furthermore, everything is protected by non-disclosure agreements. Good luck trying to be a fly on that wall.

Corporate partners

Luckily for us, we have at least some idea of who participates given their acknowledgement in the Five Eyes report. Let’s focus on a couple of lesser-known companies.

Google’s Threat Analysis Group

While Google certainly isn’t in the “lesser-known” category, perhaps its Threat Analysis Group (TAG) is. An April 2020 blog post describes the group as “a specialized team of security experts that works to identify, report, and stop government-backed phishing and hacking against Google and the people who use [their] products.”14

But it’s more than just a source of good cybersecurity advice from your run-of-the-mill techies. The author of that post, Shane Huntley, is the head of TAG, which the Wall Street Journal describes as “Google’s in-house counterespionage group.”15

TAG is staffed “partly by former government agents,” and is described as Google’s version of similar groups that also exist within Facebook and Microsoft. According to Huntley, his team is particularly focused on preventing “disinformation” from spreading on its platforms, which it accomplishes by leveraging user data from services like Gmail. In the summer of 2018, they squashed “an allegedly Iranian-backed disinformation campaign by pulling dozens of YouTube channels that were using fake accounts to push misleading political stories primarily about the Middle East.”

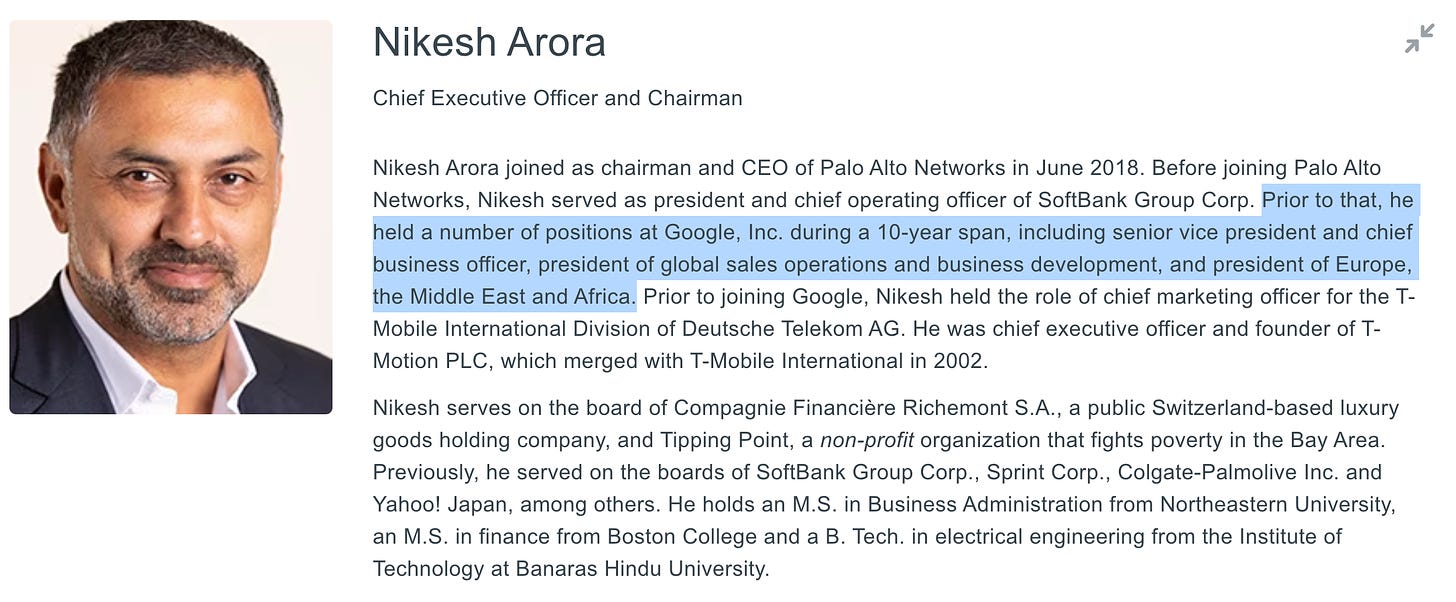

Palo Alto Networks

Palo Alto Networks is an American multinational cybersecurity company based in Santa Clara, California. I’ve previously come across the company in passing during my research on the Malala Fund to which they are a donor, alongside Apple, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Meta, the Musk Foundation, Open Society Foundations, the late Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg, and TikTok, among others.16

What I didn’t realize previously is that Palo Alto Networks’ leadership has a strong representation of former Google employees. This includes CEO and Chairman Nikesh Arora, Chief Business Officer Amit Singh, Chief People Officer Liane Hornsey, and last but not least, board member Lorraine Twohill, who currently serves as Google’s Chief Marketing Officer.17

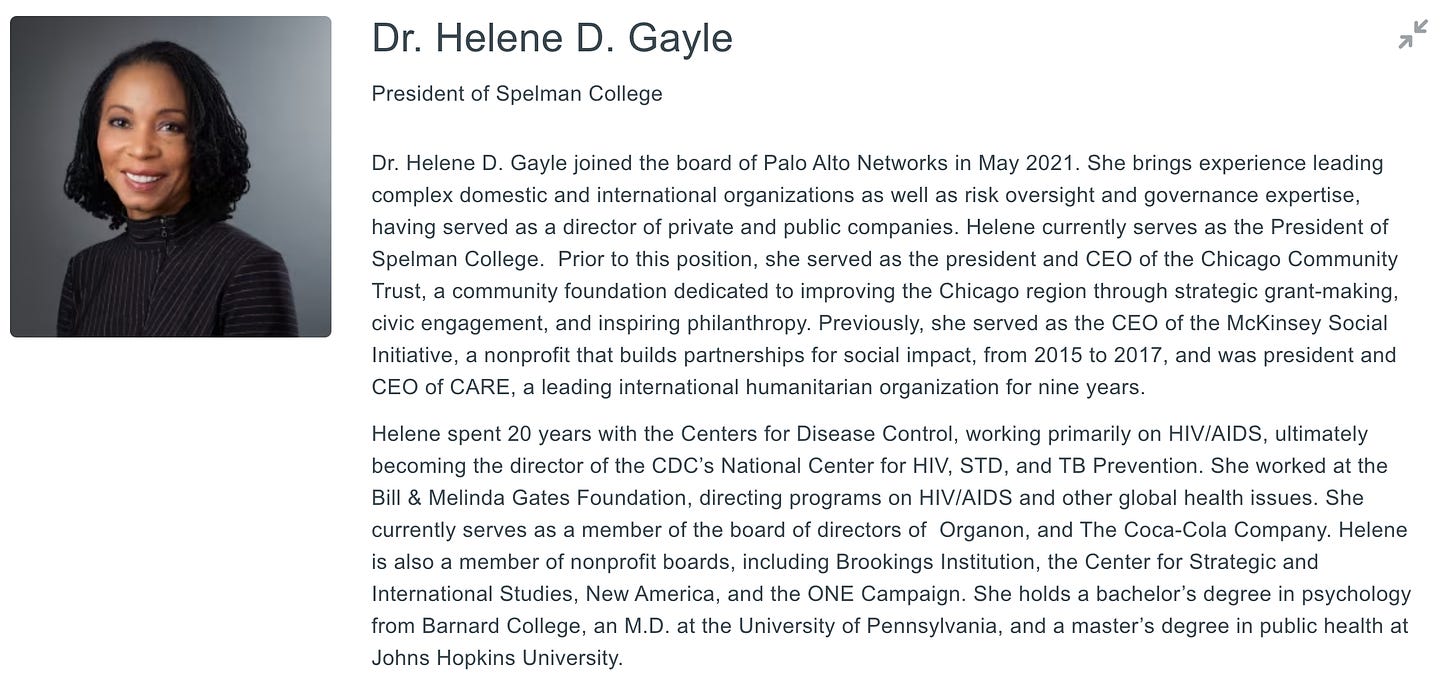

Then there’s board member Helene Gayle who “spent 20 years with the Centers for Disease Control, working primarily on HIV/AIDS, ultimately becoming the director of the CDC’s National Center for HIV, STD, and TB Prevention.” She also worked for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, “directing programs on HIV/AIDS and other global health issues.” Her portfolio also includes a board seat with pharmaceutical company Organon, and positions with a number of other prolific non-profit organizations including the Brookings Institution, the Center for Strategic and International Studies, New America, and the ONE Campaign.

Public-private partnerships

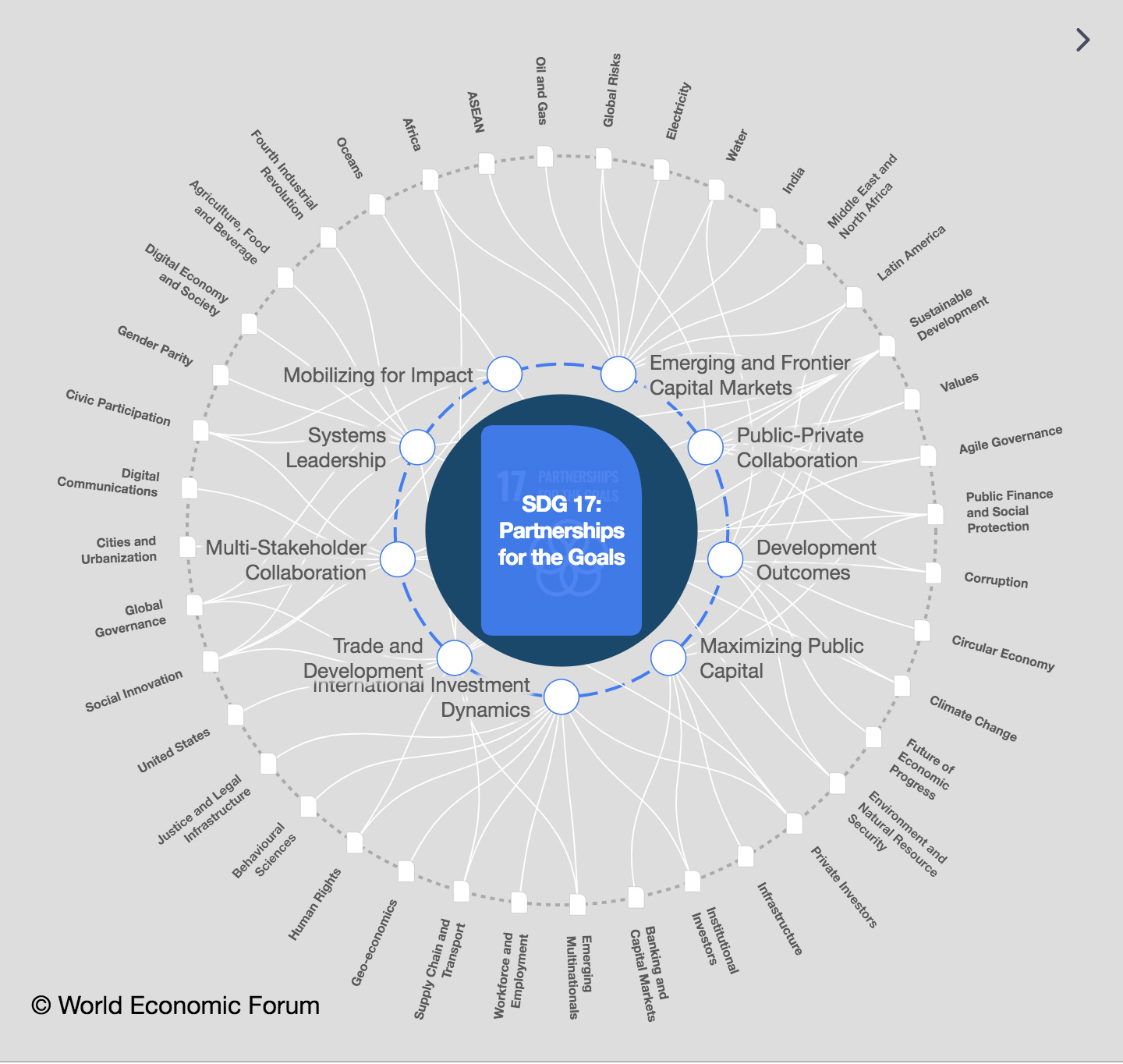

While the last few years have made it very easy to blame everything on the World Economic Forum (WEF), it is certainly true that the non-governmental organization holds significant sway over the most pressing policy decisions of today.

Notably, the WEF is the world’s biggest proponent of “public-private partnerships” (PPP). It’s not a hard concept to grasp; public-private partnerships are collaborations between governments and the private sector that are ostensibly intended to improve the status quo for people worldwide. Among the WEF’s many publications on the subject are:

Strategic Infrastructure: Steps to Prepare and Accelerate Public-Private Partnerships (April 21, 2013)

Public-private partnerships are the key to tackling climate change. Here's why (January 14, 2020)

Public-Private Partnerships for Health Access: Best Practices (December 16, 2021)

Strengthening Public-Private Cooperation with Civil Society (January 16, 2023)

…and most relevant for today’s topic:

Data and public-private partnerships are the future of cybersecurity (January 16, 2023)

Surely it’s no coincidence, then, that Amazon, Cisco, Google, Microsoft, Palo Alto Networks, Trellix, and SecureWorks’ parent company, Dell Technologies, are all partner organizations of the World Economic Forum.18

Amazon, Cisco, Microsoft, Palo Alto Networks, and Dell are also members of the WEF’s Partnership Against Cybercrime, sitting alongside government agencies like the European Commission, Europol, the FBI, INTERPOL, Israel National Cyber Directorate, Ministry of Communications and Digitalisation of Ghana, the UK’s National Crime Agency, the United States Department of Justice, and the U.S. Secret Service. According to its webpage, the Partnership Against Cybercrime “brings together a dedicated community including leading law enforcement agencies, international organizations, cybersecurity companies, service and platform providers, global corporations, and leading not-for-profit alliances” to “implement key recommendations by promoting joint research and operations processes to support and facilitate operational public-private cooperation to disrupt cybercrime.”19

But as seen with the NSA Cybersecurity Collaboration Center, public-private partnerships can also be used as a euphemistic tool to erode the barriers meant to protect citizens from overreach by both governments and private companies. Where legal boundaries exist for the public sector, these partnerships allow them to tap the private sector to accomplish a given task, and vice-versa. Again, this is not purely theoretical; this was the self-described basis for the opening of NSA’s CCC.

There’s another word often thrown around to describe this melding of state and corporate interests. A rather loaded word, in fact: fascism. To quote American political scientist and historian Robert Paxton in his reflections on fascism through modern history:20

…fascism redrew the frontiers between private and public, sharply diminishing what had once been untouchably private. It changed the practice of citizenship from the enjoyment of constitutional rights and duties to participation in mass ceremonies of affirmation and conformity. It reconfigured relations between the individual and the collectivity, so that an individual had no rights outside community interest. It expanded the powers of the executive—party and state—in a bid for total control. Finally, it unleashed aggressive emotions hitherto known in Europe only during war or social revolution.

The WEF isn’t just an unelected interest group with a lot of rich backers galavanting in Switzerland. It is that, while simultaneously acting as a formal partner with the United Nations to “deepen institutional engagement and jointly accelerate the implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” — codified in a Strategic Partnership Framework signed between the two organizations in June 2019.21

Conclusion

In the end, my message to you today is largely the same I would come to by the end of most of my episodes of Rounding the News, particularly over the last three months or so: the truth is never as simple as presented in a headline. Any headline.

Particularly in the case of geopolitical stories like this one, there’s no reason to give the benefit of the doubt to either side of the conflict. The United States and its “Collective West” allies have a long history of interfering in the autonomy of foreign governments, just like China and Russia. It is not some new premise that one side or the other engages in infiltration and deception.

Furthermore, people surely are not so naïve as to suggest our own government(s) (read: “our side”) could be the instigator in a given conflict. Or maybe it’s even more complicated than that, with neither “side” truly operating as an objective antagonist. It seems reasonable to me that the act of engaging in self-empowerment of any sort is an inherent threat to competitors, as the more powerful one nation becomes, so too does the other become more at risk.

On the other hand, it becomes more and more plausible every day that the most pressing threat to the safety and liberty of a given community is not the actions of a foreign nation, but instead, the overt, self-evident, and enthusiastic push to dissolve the lines between public governments and private corporate interests. If public institutions like healthcare, law enforcement, the military, and regulatory agencies continue to get cozier and cozier with pharmaceutical companies, big tech giants, energy producers and the news media, especially at the rate we’re going, it can only result in the total destruction of individual privacy, bodily autonomy, freedom of expression, and other God-given, non-derogable human rights.

You and I won’t solve the China-U.S. tensions overnight. But as usual, let this story serve as a reminder that there are legitimate reasons to openly engage these topics with friends and family as they come up. This helps us keep each other informed, but also allows us to build on each others’ knowledge and more quickly get to the facts of a given situation. From there, we’ll disagree a lot of the time on interpretation and what each person feels is “right” and “wrong”. That’s not a problem: that’s part of the process of learning, and of building and strengthening relationships.

And through strong relationships, we remain happy, healthy and ready to face a brand new day tomorrow.

Brand New Day

Speaking of brand new days, allow me to share with you a song of mine bearing that name!

Just prior to the COVID-19 era, I began dipping my toes into a genre that was new to me called Progressive House. Electronic music has never been my primary focus, but I’ve been a huge fan of Avicii for years and was delighted to learn that he fell into this new genre.

The process of working on these songs is different than my usual process. Instead of imagining a melody and/or lyrics then building the music on my own around the idea, I instead receive a near-complete instrumental from my Progressive House collaborators. Hearing the music for the first time, I often immediately identify a lyrical or melodic starting point and just start writing. The result: a Progressive House track featuring me as the singer.

“Brand New Day” is just such a track! It was created by a young Slovenian producer named Paxis. It’s an inspiring tune, and I had the honour of having it selected to play at my graduation from recording school at the end of 2020 (I didn’t attend the online ceremony - that’s another story for another day!) You can check out more of Paxis’ work on SoundCloud, and you can purchase the song on your platform of choice here.

Enjoy the song, and I hope you all have a fantastic week.

Microsoft Threat Intelligence. (2023, May 24). Volt Typhoon targets US critical infrastructure with living-off-the-land techniques. Microsoft Security Blog. http://archive.today/2023.05.25-103813/https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/05/24/volt-typhoon-targets-us-critical-infrastructure-with-living-off-the-land-techniques/

Goswami, R. (2023, May 24). Microsoft warns that China hackers attacked U.S. infrastructure. CNBC. http://archive.today/2023.05.24-213247/https://www.cnbc.com/2023/05/24/microsoft-warns-that-china-hackers-attacked-us-infrastructure.html

People’s Republic of China State-Sponsored Cyber Actor Living off the Land to Evade Detection. (2023, May 24). National Security Agency. https://web.archive.org/web/20230525163919/https://media.defense.gov/2023/May/24/2003229517/-1/-1/0/CSA_Living_off_the_Land.PDF

diannegali, chrisda, Dansimp, & Stacyrch140. (2023, April 20). How Microsoft names threat actors. Microsoft. http://archive.today/2023.05.17-020026/https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/security/intelligence/microsoft-threat-actor-naming?view=o365-worldwide

Sarcasm.

Lambert, J. (2023, April 18). Microsoft shifts to a new threat actor naming taxonomy. Microsoft Security Blog. http://archive.today/2023.04.19-075602/https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/security/blog/2023/04/18/microsoft-shifts-to-a-new-threat-actor-naming-taxonomy/

Secureworks Counter Threat Unit. (2023, May 24). Chinese Cyberespionage Group BRONZE SILHOUETTE Targets U.S. Government and Defense Organizations. Secureworks. http://archive.today/2023.05.25-155704/https://www.secureworks.com/blog/chinese-cyberespionage-group-bronze-silhouette-targets-us-government-and-defense-organizations

Satter, R., Pearson, J., Satter, R., & Pearson, J. (2023, May 25). Factbox: What is Volt Typhoon, the alleged China-backed hacking group? Reuters. http://archive.today/2023.05.25-211718/https://www.reuters.com/technology/what-is-volt-typhoon-alleged-china-backed-hacking-group-2023-05-25/

Satter, R. (2023, May 25). China rejects claim it is spying on Western critical infrastructure (W. Maclean, Ed.). Reuters. http://archive.today/2023.05.25-114302/https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-rejects-claim-it-is-spying-western-critical-infrastructure-2023-05-25/

Pearson, J., Satter, R., & Siddiqui, Z. (2023, May 25). U.S. State Department warns China could hack infrastructure, including pipelines, rail systems. Reuters. http://archive.today/2023.05.25-222352/https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-rejects-claim-it-is-spying-western-critical-infrastructure-2023-05-25/

NSA Cybersecurity Collaboration Center and it’s role with DIB cybersecurity. (2023, April 30). DIB Tech Talk. https://web.archive.org/web/20230525230119/https://dibtechtalk.com/blog/post/2066656/nsa-cybersecurity-collaboration-center-and-it-s-role-with-dib-cybersecurity

Smalley, S. (2022, November 16). “No guns, no guards, no gates.” NSA opens up to outsiders in fight for cybersecurity. CyberScoop. http://archive.today/2023.03.22-155024/https://cyberscoop.com/nsa-threat-sharing-unclassified-ccc/

Bing, C. (2021, June 22). Amid big hacks, U.S. spy agency touts collaboration center with private industry. Reuters. http://archive.today/2021.06.22-214702/https://www.reuters.com/technology/amid-big-hacks-us-spy-agency-touts-collaboration-center-with-private-industry-2021-06-22/

Huntley, S. (2020, April 22). Findings on COVID-19 and online security threats. Google. http://archive.today/2021.05.08-070950/https://blog.google/threat-analysis-group/findings-covid-19-and-online-security-threats/

McMillan, R. (2019, January 23). Inside Google’s Team Fighting to Keep Your Data Safe From Hackers. Wall Street Journal. http://archive.today/2020.01.01-143527/https://www.wsj.com/articles/inside-googles-team-battling-hackers-11548264655

Partners. Malala Fund. Retrieved June 28, 2022, from http://archive.today/2022.06.28-152102/https://malala.org/partners

Management. Palo Alto Networks. Retrieved March 21, 2023, from https://web.archive.org/web/20230321081604/https://www.paloaltonetworks.ca/about-us/management

Partners. World Economic Forum. Retrieved May 26, 2023, from https://web.archive.org/web/20230526015352/https://www.weforum.org/partners

Partnership against Cybercrime. World Economic Forum. Retrieved May 26, 2023, from https://web.archive.org/web/20230526201058/https://www.weforum.org/projects/partnership-against-cybercime

Paxton, R. O. (2004). The Anatomy of Fascism (p. 11). Vintage Books.

Tedeneke, A. (2019, June 13). World Economic Forum and UN Sign Strategic Partnership Framework. World Economic Forum. http://archive.today/2023.01.07-201341/https://www.weforum.org/press/2019/06/world-economic-forum-and-un-sign-strategic-partnership-framework/

Thank you - good piece.

They spent years warning us of coming pandemics and now we are told to fear AI and cyberattacks.

I guess this is how they let us know what their plans are.